- Clayton's Newsletter

- Posts

- Wednesday Wisdom

Wednesday Wisdom

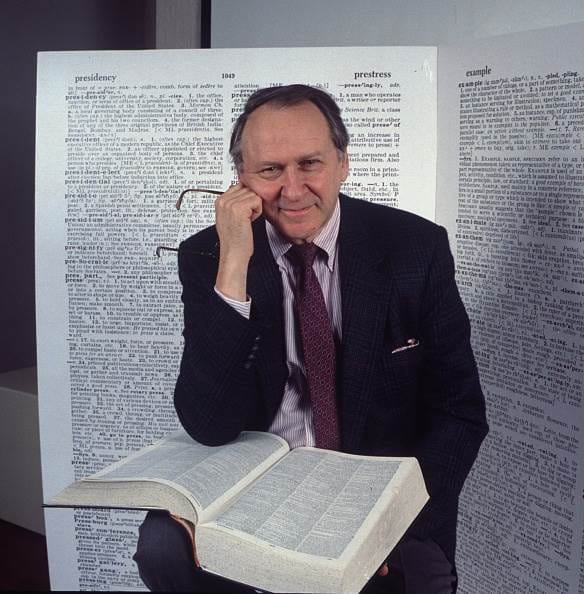

Does Bad Grammar Lead to Poor Thinking? Are Weasel Words Manipulating Your Thoughts? The Language "Maven" William Safire Will Tell You the Truth

William Safire was born William Lewis Safir, December 17, 1929, in New York City and was known as an influential American author, columnist, journalist, and presidential speechwriter. Safire attended Syracuse University but left after his sophomore year. He began his professional life as a reporter and later became a prominent figure in public relations. In 1959, he orchestrated the famous "Kitchen Debate" between Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in Moscow while working as a public relations executive. Nixon took part of the American National Exhibition in Sokolniki Park, Moscow which was a major cultural and propaganda event held in the summer of 1959. Essentially, it was the U.S. government's attempt to showcase the American way of life to Soviet citizens during the height of the Cold War. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, being on his home turf, was aggressive in defending Soviet Communism in the filmed discussions with Nixon. At one point Nixon trying to find some common ground mentioned that his father had owned a small general store. Khrushchev retorted, "Oh, all shopkeepers are thieves," putting Nixon on the defensive and forcing Nixon to aggressively defend his background and the integrity of American small business owners. Safire brilliantly decided their next discussion should be in a model kitchen that was being displayed showing the innovative inventions available for American families. The reason the final "Kitchen Debate" portion is remembered as a success for Nixon is that he was able to shift the focus from military, space, and high politics where the Soviets had recent bragging rights, like the Sputnik satellite to the tangible benefits of American capitalism and consumer culture and in turn save his Presidential aspirations for 1960.

Safire went on to serve as a special assistant and senior speechwriter for President Richard Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew from 1969 to 1973. He is famously credited with coining the phrase "nattering nabobs of negativism" for a speech delivered by Agnew. He also drafted the never-delivered speech, "In Event of Moon Disaster," for President Nixon in case the Apollo 11 astronauts were stranded.

After leaving the White House, Safire joined The New York Times in 1973 as a political columnist, presenting a libertarian conservative viewpoint. He wrote his twice-weekly political "Essay" column for 32 years. In 1978, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished commentary for his reporting on the banking scandal involving Bert Lance who was President Jimmy Carter's budget director.

Safire may be most fondly remembered for his column On Language for The New York Times Magazine which was published every Sunday from 1979 until his death in 2009. He explored etymology which is the origin and evolution of words, grammar, and usage, earning him the nickname "language maven." The term “maven” is Yiddish for expert or enthusiast, a role he was objectively filled both language and grammar.

His column could be both brilliant and condescending while engaging with lesser wordsmiths, often using sarcasm or wry to bring discussion and thought. He was also keen to police poor word choice or grammar but more importantly acted as a sage to those who wanted to expand their vocabulary, honor the written word or improve their grammar. God forbid one would make the grammar mistake and misuse “imply” or “infer”.

As a proponent and teacher of language, he included a “Socratic Approach” under the heading "Queries, Quibbles, and Quiddities" by reaching out to his readers through mail. Safire structured the column as a conversation, citing questions, critiques, and suggested usage from his audience. This created an interactive forum where readers felt they were part of the linguistic debate, rather than simply being lectured to.

Safire also authored numerous books, including historical novels, thrillers, and collections of his language columns and political dictionary, Safire's Political Dictionary. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2006.

Safire's long career was marked by his dual reputation as both a fiercely opinionated conservative political commentator and a witty, insightful expert on the English language. Part of the On Language column’s appeal was that it was not politically correct and offered a strong, sometimes abrasive, personality. Readers often wrote in precisely because they enjoyed the high-stakes, competitive, and potentially humiliating experience of engaging in a public linguistic debate with the famous columnist.

Safire used an epistemological approach to explain how words can influence thought and truth. He believed clear language was essential for attaining reliable knowledge and poor, muddy and manipulative language brought the same kind of thinking. He also utilized logic to undermine “rhetorical fallacies” which are linguistic tricks such as euphemisms, loaded language, “weasel words” and ambiguity that sought to undermine the truth. For example, a euphemism would be instead of “firing someone” one would say “a reduction in force”. Instead of saying a “tax cut”, using the term “tax relief” appealed to emotions and away from facts. Safire regularly pointed out "weasel words" or vague terms like “perhaps, many, some experts believe” that politicians use to make claims sound authoritative while avoiding firm, verifiable commitments, thereby protecting their statements from logical refutation.

William Safire’s On Language remains as the model for how a newspaper column can inform, educate and entertain will fostering a dialogue. Safire’s column and books were not only popular and read by millions, but his work was also iconic in influencing a generation to understand the power of language and the written word.

P.S. I shudder not shutter to think of Safire’s critique.

And now you know...

Thanks, Dad, for the gift of curiosity!

Philosophy is the art of thinking, the building block of progress that shapes critical thinking across economics, ethics, religion, and science.

METAPHYSICS: Literally, the term metaphysics means ‘beyond the physical.’ Typically, this is the branch that most people think of when they picture philosophy. In metaphysics, the goal is to answer the what and how questions in life. Who are we, and what are time and space?

LOGIC: The study of reasoning. Much like metaphysics, understanding logic helps to understand and appreciate how we perceive the rest of our world. More than that, it provides a foundation for which to build and interpret arguments and analyses.

ETHICS: The study of morality, right and wrong, good and evil. Ethics tackles difficult conversations by adding weight to actions and decisions. Politics takes ethics to a larger scale, applying it to a group (or groups) of people. Political philosophers study political governments, laws, justice, authority, rights, liberty, ethics, and much more.

AESTHETICS: What is beautiful? Philosophers try to understand, qualify, and quantify what makes art what it is. Aesthetics also takes a deeper look at the artwork itself, trying to understand the meaning behind it, both art as a whole and art on an individual level. A question an aesthetics philosopher would seek to address is whether or not beauty truly is in the eye of the beholder.

EPISTEMOLOGY: This is the study and understanding of knowledge. The main question is how do we know? We can question the limitations of logic, how comprehension works, and the ability (or perception) to be certain.